(1904 - 1972)

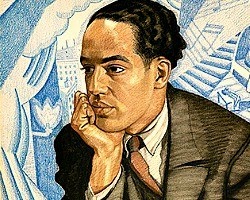

Anglo-Irish poet Cecil Day Lewis, who with Auden and Spender was thought of as forming the original political-cum-poetical triumvirate of the thirties, was born in Ireland in 1904 and educated at Sherborne School and Wadham College, Oxford. He edited Oxford Poetry with Auden in 1927, and, after leaving the university, became a schoolmaster in turn at Oxford, Helensburgh, and Cheltenham until 1935. He was employed at the Ministry of Information during the war. Since then he has been occupied with writing, lecturing, and broadcasting. He became Professor of Poetry at Oxford in 1951 (being Auden's immediate predecessor in his position). The Buried Day (1960) is an autobiographical account of the earlier part of his life. It is worth reading (although inferior in candor and insight to Stephen Spender's World Within World) and Poet Laureate in 1968.

He is primarily a poet, but he also wrote novels, detective fiction (under the pseudonym of Nicholas Blake), and stories for children. He wrote 25 novels, most of which were signed under the pen name Nicholas Blake. He confirmed himself as a master of crime and detective novels. In his novel The Sad Variety (1964) he showed his discontent with the course of Communism in the Soviet Union. This novel represents his breakup with Communism. He also wrote much criticism. His criticism includes A Hope for Poetry(1934);Poetry for You (1945), a book which was popular in schools; The Poetic Image (1947), which is the published form of his Clark Lectures at Cambridge; and Notable Images of Virtue (1954). His 1951 Warton Lecture, The Lyric Poetry of Thomas Hardy, has a special interest for readers of his poems.

|

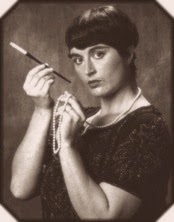

| From left to right: W. H. Auden, Cecil Day Lewis and Christopher Isherwood |

Stephen Spender said that Day Lewis was a poet "who is least sure of himself when he writes of his immediate feelings". This statement can be accepted if such lyrics as "Marriage of Two" and "The Woman Alone" (from Poems 1943-1947) can be taken as exceptions proving the rule. It is true that as a personal lyric poet he often fumbles and produces blurred or trite effects. His abilities as a translator or as a narrative poet —a good specimen is "The Nabara" from Overtures to Death— can rarely be questioned in this way. Poems 1943-1947 contains an excellent example of translation in "The Graveyard by there Sea", a version of Paul Valéry's Le Cimetière Marin. The parodies or imitations of Hardy, Yeats, Frost, Auden, and Dylan Thomas in An Italian Visit are further illustrations of a surprising poetic versatility. There is no real falling-off in quality in Pegasus and Other Poems—for many years now Day Lewis has been a remarkably consistent poetic performer. Anne Ridler notes of this last volume that it contains poems "generated at a low poetic temperature", but this criticism can be applied to volumes published in the thirties and forties and connects with the "professionalism" that the same critic comments on respectfully.

In brief it may be said that Day Lewis's failures are verbal, his successes rhythmical. This is a simplification, but the greater pleasure to be derived from his later volumes is more due, I think, to an increased power of making rhythmical patterns than to any change in subject-matter or deepening of sensibility. It is also worth mentioning his political commitment with the Spanish Civil War. He served as a partisan supporting the Republican Army. His books of poems: Overtures to Death (1938) is a manifest of his bitter memories during the Spanish Civil War and the rise of Fascism in Europe. "The Nabara" was the most significant poem he wrote inspired by the Spanish conflict. The long poem is the core of his book of poems Noah and the Waters (1947). In the late thirties he became so disillusioned with Communism that he abandoned his party membership and his leftish political ideas. He died on 22 May 1972, at Lemmons (Hertfordshire, England).

Nota Bene: The episode upon which this poem is based is related in G. L. Steer's The Tree of Gernika.

They preferred, because of the rudeness of their heart, to die rather than to surrender

Phase One

Freedom is more than a word, more than the base coinage

Of statesmen, the tyrant's dishonored cheque, or the dreamer's mad

Inflated currency. She is mortal, we know, and made

In the image of simple men who have no taste for carnage

But sooner kill and are killed than see that image betrayed.

Mortal she is, yet rising always refreshed from her ashes:

She is bound to earth, yet she flies as high as a passage bird

To home wherever man's heart with seasonal warmth is stirred:

Innocent is her touch as the dawn's, but still it unleashes

The ravisher shades of envy. Freedom is more than a word.

I see man's heart two-edged, keen both for death and creation.

As a sculptor rejoices, stabbing and mutilating the stone

Into a shapelier life, and the two joys make one-

So man is wrought in his hour of agony and elation

To efface the flesh to reveal the crying need of his bone.

Burning the issue was beyond their mild forecasting

For those I tell of - men used to the tolerable joy and hurt

Of simple lives: they coveted never an epic part;

But history's hand was upon them and hewed an everlasting

Image of freedom out of their rude and stubborn heart.

The year, Nineteen-thirty-seven: month, March: the men, descendants

Of those Iberian fathers, the inquiring ones who would go

Wherever the sea-ways led: a pacific people, slow

To feel ambition, loving their laws and their independence-

Men of the Basque country, the Mar Cantabrico.

Fishermen, with no guile outside their craft, they had weathered

Often the sierra-ranked Biscayan surges, the wet

Fog of the Newfoundland Banks: they were fond of pelota: they met

No game beyond their skill as they swept the sea together,

Until the morning they found the leviathan in their net.

Government trawlers Nabara, Guipuzkoa, Bizkaya,

Donostia, escorting across blockaded seas

Galdames with her cargo of nickel and refugees

From Bayonne to Bilbao, while the rest of war curled higher

Inland over the glacial valleys, the ancient ease.

On the morning of March the fifth, a chill North-Wester fanned them,

Fogging the glassy waves: what uncharted doom lay low

There in the fog athwart their course, they could not know:

Stout were the armed trawlers, redoubtable those who manned them-

Men of the Basque country, the Mar Cantabrico.

[...]

[Fragment from the long poem "The Nabara" (Noah and the Waters)]

Do not expect again a phoenix hour,

The triple-towered sky, the dove complaining,

Sudden the rain of gold and hear's first ease

Tranced under trees by the eldritch light of sundown.

By a blazed trail our joy will be returning:

One burning hour throws light a thousand ways,

And hot blood stays into familiar gestures.

The best years wait, the body's plenitude.

Consider then, my lover, this is the end

Of the lark's ascending, the hawk's unearthly hover:

Spring season is over soon and first heatwave;

Grave-browed with cloud ponders the huge horizon.

Draw up the dew. Swell with pacific violence.

Take shape in silence. Grow as the clouds grew.

Beautiful brood the corn lands, and you are heavy;

Leafy the boughs-they also hide big fruit.

Websites:

Cecil Day-Lewis Official Website

On "A Hope for Poetry"

Some Online Poems

C. S. Lewis as Poet

Poet Laureate

Poetry Foundation

"Do not Expect Again a Phoenix Hour" read by Cecil Day Lewis

En español:

Noticia en español sobre su hijo, el actor Daniel Day-Lewis

Poema "El voluntario" ("The Volunteer") en español.

Bibliography:

Cecil Day Lewis 1938: Overtures to Death and Other Poems. London: J. Cape.

—————— 1947: Noah and the Waters. New York: Transatlantic Arts.

——————— 1979: Collected Poems. London: Hyperion.

——————— 2002 (1960): Studies in Words. Cambridge: CUP.

Nicholas Blake (C. Day-Lewis) 1979: The Sad Variety. London: Harper Collins.

Albert Gelpi 1997: Living in Time: The Poetry of Cecil Day Lewis. Oxford: OUP.

Peter Stanford 2007: C. Day-Lewis: A Life. London: Bloomsbury.

En español:

Niall Binns 2004: La llamada de España: Escritores extranjeros en la Guerra Civil. Madrid: Montesinos.

.jpg)